In the life sciences world, the profession of validation is all about risk reduction. Validation professionals have a mission to identify areas of risk associated with making and managing therapies from the supply chain through delivery to patients. Naturally, validation professionals need several key categories of information to be successful with this mission:

- Understand what aspects of ingredients, intermediates, and final product must be controlled to ensure safety to the patient and efficacy to the product

- Determine what processes need to be in place to demonstrate their company is operating in a demonstrably controlled manner

- Set up a structured program of risk assessment and testing to verify that risk is identified and either engineered or tested down to an acceptable level

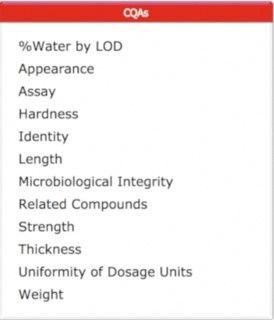

Number 1 above is identified by a life science company’s regulatory and quality personnel. These are the critical-to-quality attributes (CQAs) that are explicitly called out in the Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Control section of electronic Common Technical Documents (eCTDs.) The eCTD format is the format required by the United States and European Union for regulatory filings. CQAs are attributes such as product strength or microbial contamination that must fall within specified parameters to ensure product integrity for patients. Here are examples from our risk management application of some CQAs associated with a solid dosage product:

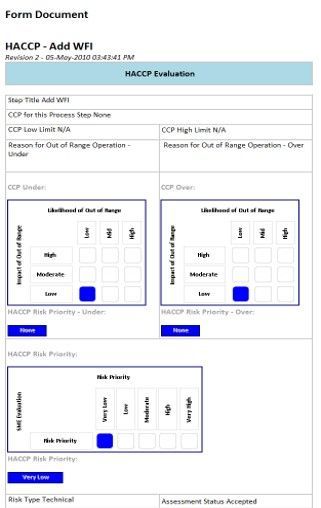

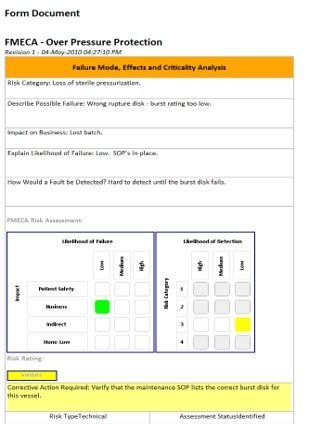

Were there a CQA associated with this step, then it would be cited. Perhaps there is not CQA at risk…perhaps safety, control, efficiency, cost, or some other risk is identified. Some people might choose Failure Mode Effects and Criticality Analysis (FMECA) to assess equipment, with the same purpose:

Both forms shown above have important fields to be filled out and modified over time. Yes, the obvious assessment itself, but note that the level of risk that come out of the assessment dictates (per your company’s policy) whether commissioning or validation is required to test out that risk. Or, possibly, the risk level may be so high that your company may mandate that systems and/or processes be re-engineered so as to reduce risk. And, also note that risk assessments themselves have status (per ICH) as shown in next image.

- Identified

- Evaluated

- Analyzed

- Accepted

At the end of this risk assessment process is the use of ASTM E2500-07 (Standard Guide for Specification, Design, and Verification of Pharmaceutical and Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing Systems and Equipment) to capture specifications and testing in an organized manner but also to ensure commissioning and validation is managed efficiently. This ASTM standard boils down to, essentially:

- Test specifications once (if possible)

- Test specifications only as rigorously as needed

In practice, if what a specification describes is assessed at low risk and will not impact safety or a CQA then it may be testing once in commissioning. For example, clean stainless pipe may be checked once for clean welds and legitimate material certifications during an FAT. However, if a specification impacts a CQA or safety, or even is assessed at a high risk or perhaps is changeable, then it will need to be validated (and probably re-validated on some schedule.)

Traditionally, companies have commissioned AND validated everything – often several times. ASTM E2500-07, informed by the rigorous risk assessments done above, helps companies not only reduce the cost of testing – but makes testing more effective and enables companies to demonstrate to regulatory agencies that it can show exactly where the CQAs referenced in their eCTDs are potentially impacted by their processes and systems.

Were there a CQA associated with this step, then it would be cited. Perhaps there is not CQA at risk…perhaps safety, control, efficiency, cost, or some other risk is identified. Some people might choose Failure Mode Effects and Criticality Analysis (FMECA) to assess equipment, with the same purpose:

Both forms shown above have important fields to be filled out and modified over time. Yes, the obvious assessment itself, but note that the level of risk that come out of the assessment dictates (per your company’s policy) whether commissioning or validation is required to test out that risk. Or, possibly, the risk level may be so high that your company may mandate that systems and/or processes be re-engineered so as to reduce risk. And, also note that risk assessments themselves have status (per ICH) as shown in next image.

In practice, if what a specification describes is assessed at low risk and will not impact safety or a CQA then it may be testing once in commissioning. For example, clean stainless pipe may be checked once for clean welds and legitimate material certifications during an FAT. However, if a specification impacts a CQA or safety, or even is assessed at a high risk or perhaps is changeable, then it will need to be validated (and probably re-validated on some schedule.)